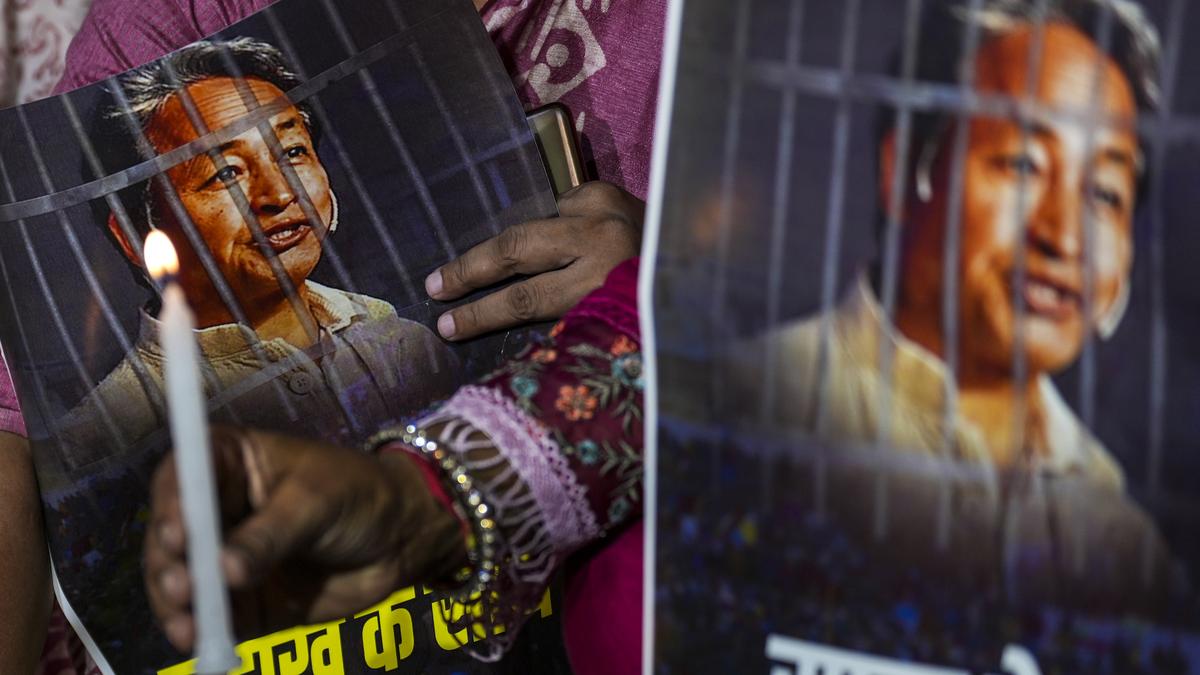

Agitators hold posters and a candle during a protest over the arrest of climate activist Sonam Wangchuk, at Jantar Mantar, in New Delhi, on Friday, September 26, 2025.

| Photo Credit: PTI

The crucial legal issue behind the detention of climate activist Sonam Wangchuk under the National Security Act (NSA) is whether the authorities applied their minds to the relevant material to reach the “requisite subjective satisfaction” that his activities are prejudicial to public order or the security of the state.

Mr. Wangchuk is reported to have been on a hunger strike for Statehood and Sixth Schedule status for the Union Territory of Ladakh. He was detained under the provisions of the NSA on September 26 after police action against violent protests in Leh that left four civilians dead.

The Supreme Court has differentiated between breach of ‘law and order’ and violation of ‘public order’. The latter refers to actions which affect the community or the public at large.

“Public order is the even tempo of life of the community taking the country as a whole or even a specified locality,” the court has observed in its reported 2024 judgment in Nenavath Bujji Vs. State of Telangana.

‘Law and order’ has a wider ambit. A fight between two drunks in a public place is an act in contravention of law and order. ‘Public order’ has a narrower radius — the alleged act must have impacted the country as a whole, or the locality.

“The distinction between the areas of ‘law and order’ and ‘public order’ is one of degree and extent of the reach of the act in question on the society,” the apex court said in its July 2025 decision in the NSA case of Annu @ Aniket Vs. Union of India.

The NSA empowers the Centre and States to detain individuals to prevent them from acting in a manner “prejudicial to the defence of India, relations with foreign powers, the security of India, or the maintenance of public order or essential supplies”.

However, the court has, in a series of decisions, made it clear that the detaining authority should “justify the detention order from the material that existed before him and the process of considering the material should be reflected in the order of detention while expressing its satisfaction”.

It has laid down guidelines for authorities using their subjective satisfaction to detain under the NSA, including the taking into consideration of “only relevant and vital material” to arrive at the requisite subjective satisfaction; the implicit duty to apply their minds to pertinent and proximate matters and eschew those which are irrelevant and remote — the courts can examine whether the subjective satisfaction of the authority was based on objective facts or influenced by any caprice, malice or irrelevant considerations or non-application of mind.

The apex court has consistently held that “preventive detention of a person is a drastic measure and an order of preventive detention has the effect of invading a person’s personal liberty”. Therefore, the detaining authority should exercise the “hard law” of detention with utmost caution.

The court has highlighted that the inability of the state machinery to “tackle a law and order situation should not be an excuse to invoke the jurisdiction of preventive detention”. The court has held that even habitual criminality cannot be the sole basis for preventive detention.

The courts are skeptical of the use of what is called the ‘broken windows theory’, a criminological theory which has material bearing in the realm of prosecution, adjudication, and specially for preventive measures, including the NSA. The idea behind the theory is that “if a window in a building is broken and left unrepaired, all of the windows would soon be broken”, that is, the detention of one person to send across a message of deterrence to that individual and other probable perpetrators.

Published – September 28, 2025 03:28 am IST