Ghatam player Sumana Chandrashekar’s book, My Journey with the Ghatam: Song of the Clay Pot (Speaking Tiger) is more than a memoir — It is a critical exploration of the layered histories of Indian music, performance and cultural memory. The book, while tracing the author’s journey with the ghatam pushes the boundaries of autobiographical writing. Apart from her experiences with the instrument, Sumana interrogates the broader structures — social, gendered and political — that have shaped ghatam’s place within Indian classical music traditions.

Traditionally played by men, ghatam is referred to as the upa pakkavadyam (secondary accompanying instrument) in the Carnatic music hierarchical structure. Sumana’s inquiry leads to voices that have been amplified and those that have been silenced. She also questions musical practices that have become entrenched over time, while drawing attention to others that have been erased or pushed to the margins. At the heart of this work lies the tension between memory and history. The ghatam, a clay pot percussion instrument, serves as a powerful metaphor in this exploration: an object of both sound and silence, presence and marginality, patriarchy and power.

While the book engages with similar themes that many earlier works on music have tackled, it highlights how different truths emerge depending on the vantage point. By revisiting history through diverse perspectives, especially those of women and marginalised voices, it not only offers fresh insights but also the tools to understand and navigate the present with greater sensitivity.

Breaking stereotypes

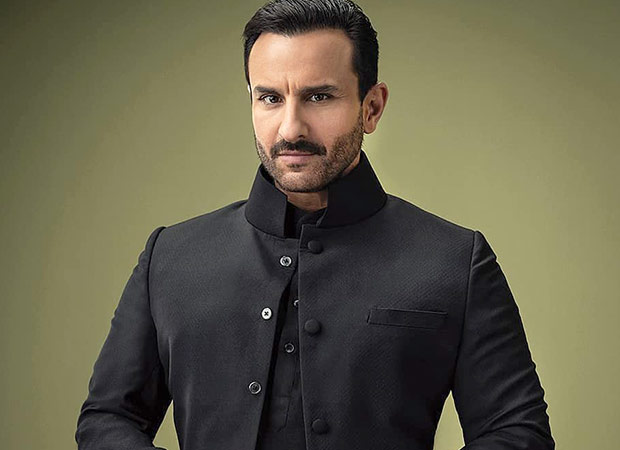

The book cover.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The opening chapters chart the author’s inward journey from Carnatic vocal to the ghatam, a transition prompted by a recurring dream in the summer of 2008. She writes with exhaustive detail about her guru, the textures of apprenticeship, the stalwarts of percussion and the legends of great masters. The reflections are sincere, and at times, illuminating, harking back to ideas of discipline, body and spirit.

Under Sukanya Ramgopal’s tutelage, Sumana encounters not just a master of rhythm but a woman of quiet strength and rare humanity. Sukanya’s choice of the ghatam came at a time when a woman percussionist was an anomaly, often met with hostility. Guided by two visionaries — Harihara Sharma and his son, Vikku Vinayakram — she weathered repeated slights from senior musicians and organisers. None of this dimmed her devotion. The presence of these three artistes and how they helped her navigate a world steeped in prejudice, infuses the narrative with warmth and dignity, while inviting reflection on gender and art — reminiscent of the nattuvanar–Devadasi dynamic.

Juxtaposed with this is the story of Meenakshi of Manamadurai — a woman from a lower rung of the social hierarchy, whose labour quite literally gives form and voice to the instrument. It is her hands that bring the tonal perfection to the ghatam through days of physically demanding work, yet her contribution remains invisible to the world that reveres its sound. She sits in solitude, in quiet meditativeness, shaping the clay with instinctive precision. The media, she observes, once sought her husband’s words, and now her son’s; her own voice, as ever, remains unheard. Meenakshi’s story becomes a counter-image to Sukanya’s — one of creation without recognition, devotion without visibility — reminding us how art’s hierarchies extend beyond performance into the very making of sound itself.

Intriguing questions

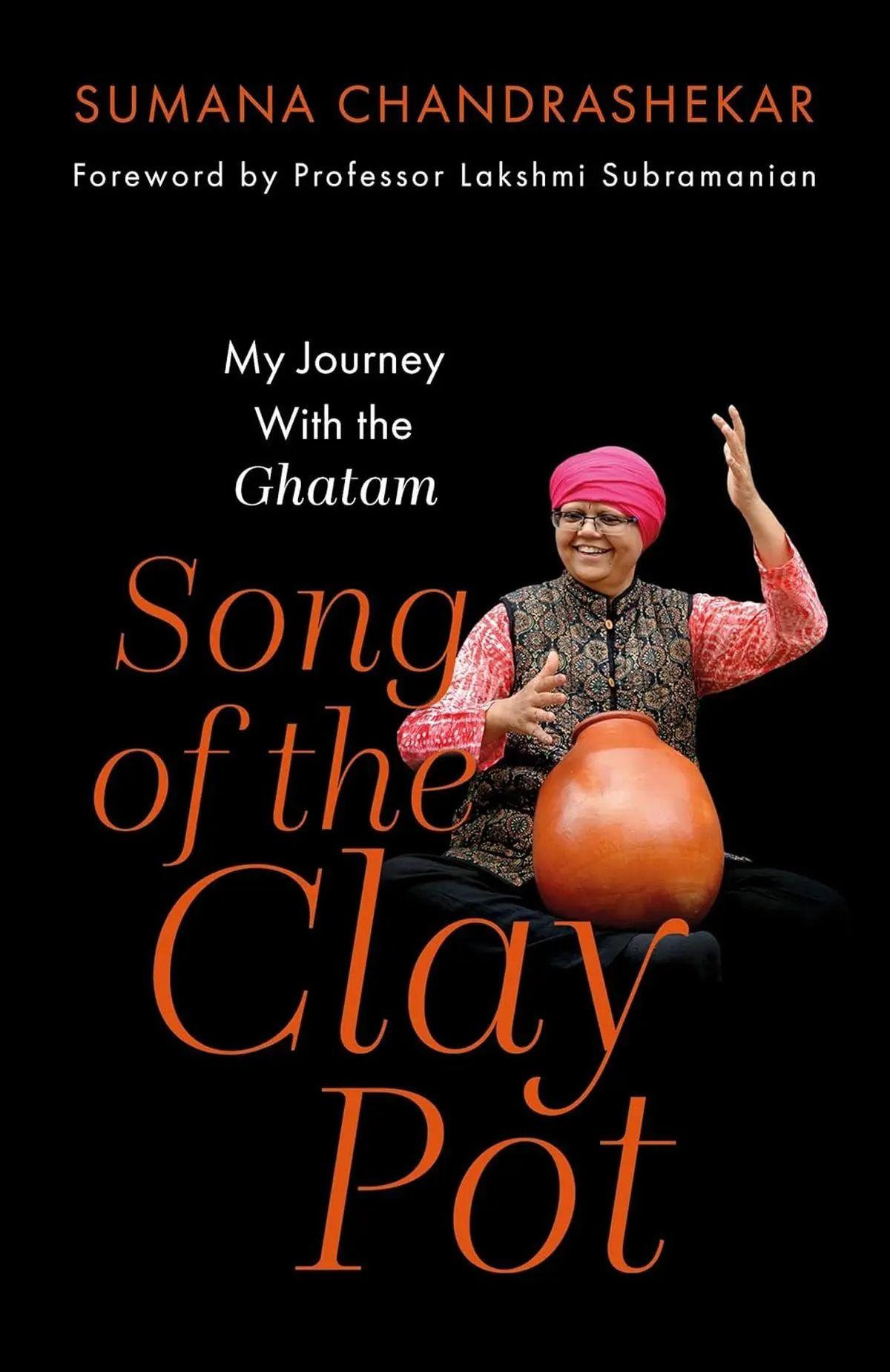

The ghatam helped Sumana find her musical identity

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

From within these layered portraits, Sumana’s own persona gradually takes shape — through anecdotes of misogyny, patriarchy and the scrutiny of appearance. Her understanding of success and failure often seems refracted through the expectations of the world around her. In the present, she appears less prepared to meet the challenges that arise, perhaps because, as products of our time, we assume the world should be fair and just, though it remains far from it. Out of this realisation emerges one of the book’s most thought-provoking questions: M.S. Subbulakshmi, Sumana recalls, was a competent mridangam player before she chose to be a vocalist. Had she continued as a percussionist, would the story of women in percussion have unfolded differently? It is a question that haunts her, torn as she is between remaining with the ghatam or leaving it behind — until her guru reminds her that what truly sustains an artiste is not validation from the world, but the ‘inner fire’.

The final chapters of the book are meticulously researched, with sections such as ‘Musical Censorship’, ‘The Phoenix Rises’ and ‘On Pot Bellies’ offering particularly engaging reading. Drawing from a variety of sources, Sumana presents her findings thoughtfully. For instance, the semi-circular concert seating of the past is back in practice today, not only addressing hierarchy on stage but also allowing the upa pakkavadyam artiste to establish eye contact with the main performer, correcting a subtle disadvantage. There are many such instances throughout the book.

From where we stand, however, it is worth approaching our observations with a certain tentativeness. Isn’t that why we should revisit history from time to time? The book invites reflection not on simple binaries of right and wrong, or on a wholly rigid and unfeeling social order, but on the complexities that lie beyond our immediate understanding. There were spaces where gender and hierarchy were temporarily suspended, and moments of genuine partnership emerged. Yet, these moments coexisted with absences, gaps, and unacknowledged tensions — patterns whose causes may be obscured, reminding us not to draw easy conclusions. In this sense, the book leaves us with a quiet, probing question: how do we reckon with what is partly visible, partly intangible, and always lived?

The memoir insists on the importance of continually revisiting cultural narratives, not to destabilise tradition, but to illuminate its many layers—and to make space for more inclusive musical futures.

Published – October 23, 2025 01:42 pm IST