I’m late to the Train Dreams discourse, but the film found me right after a quick escape into the hills. I spent part of that trip hugging a tree that briefly unplugged me from the horrors of the daily grind. So when the film opened with a montage through those lush greens, the textures felt uncannily familiar, like the oaks were still whispering whatever ancient secret they tried to tell me. It also gave William H. Macy’s line some added weight: “Beautiful, isn’t it?… all of it.” Despite the title, Train Dreams isn’t really about trains at all. It wanders through the forest with a dazed, off-kilter clarity of a mild psychedelic that’s basically catnip for tree nerds and outdoorsy purists. But its true agenda felt simpler (and concerningly pointed): shut your laptop, go outside, and for the love of God, touch some grass.

This is a modest story about the life of Robert Grainier (Joel Edgerton), an orphan who drifts into adulthood as an Idaho labourer and dies eighty years later in the same region, with his name destined to vanish into the soil he worked. Director Clint Bentley treats that ordinariness as the entire point. We move through fifty years of Robert’s life in clean, lucid sweeps. Bentley and co-writer Greg Kwedar (of Sing Sing acclaim) lean hard into third-person narration, borrowing the idea from Jules et Jim and Y Tu Mamá También; and Will Patton’s voice has that gravelly, front-porch cadence that could sell almost anything.

Train Dreams (English)

Director: Clint Bentley

Cast: Joel Edgerton, Felicity Jones, William H. Macy, Kerry Condon, Nathaniel Arcand

Runtime: 102 minutes

Storyline: Robert Grainier lives all of his years in the forests of the Pacific Northwest, working on the land, helping to create a new world at the turn of the 20th century

The structure is openly novelistic with short, dense chapters of time rather than traditional arcs. We see Robert deposited in Idaho, folded into logging camps and rail gangs; then we’re in the riverside cabin with his wife Gladys (Felicity Jones) and their daughter; then alone again in the woods with ghosts of the past. When the film trusts this memory logic and lets images carry the cuts, it feels genuinely shaped by an old man’s flickering recall.

As a portrait of labour, the film is remarkably specific. Adolpho Veloso shoots the manual choreography of logging with saws biting into bark and men leaning into the teeth of the blade with tired muscle memory coordination. These men build the infrastructure of the century and vanish into it. We understand that Robert’s body is being used up on behalf of forces he’ll never meet, and Bentley is good at placing him inside these extractive systems.

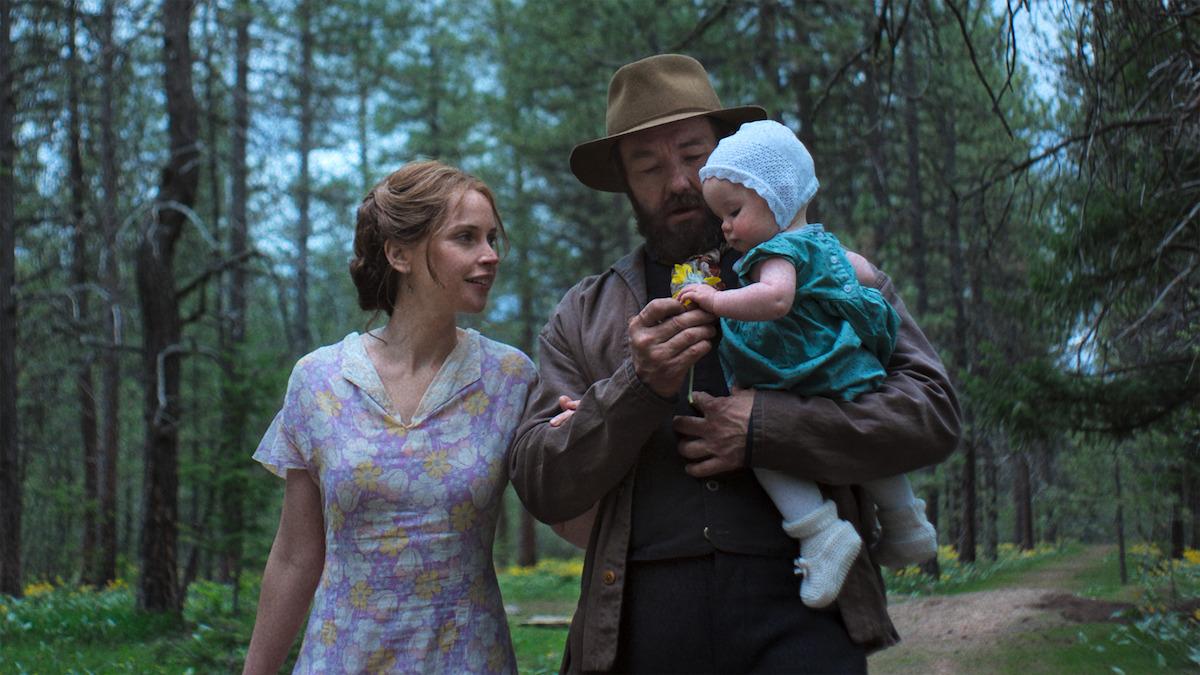

A still from ‘Train Dreams’

| Photo Credit:

Netflix

William H. Macy’s Arn Peeples, explosives man and camp philosopher, rambles around the fire about five-hundred-year-old trees and the spiritual cost of cutting them down. Kerry Condon’s Claire, turning up in Robert’s later years with Forestry Service maps and glacier history, extends that thought into a worldview. The two nudge the film toward a soft indictment of manifest destiny and the ecological cost of progress; and there is a sense that every shot of sunlight filtering through branches is in direct conversation with the slow violence of capital.

But the incident on the bridge with the Chinese worker is where the film’s nerves show. In Johnson’s novella, Grainier is complicit in the attempted killing; the man survives and the memory festers. In Bentley’s version, the worker is dragged out, beaten and thrown off a bridge, and Robert’s role is strategically softened. He merely asks what the man has done, half-steps forward, gets shoved aside and forever carries the guilt of inaction. The worker dies and returns sporadically as an accusatory apparition. The shift feels unwarranted and undermined, because now a white labourer who participated becomes a white labourer who wished he had done more, and the Chinese character goes from a figure in a knot of economic fear and racism to an almost wordless instrument of Robert’s moral development. Add the brief earlier scene of mass deportation of Chinese families, narrated as something that “baffled” young Robert, and you get a consistent pattern of racial violence witnessed with survivors guilt rather than the very structure he moves inside of. Johnson was interested in how terrible stories curl around the edges of ordinary men’s lives, but Bentley seems to prefer a version of the world in which the horror sits safely offscreen, so the melancholy can keep its glow.

Inside that curated frame, Train Dreams can be genuinely overwhelming. The courtship between Robert and Gladys, has an unshowy warmth that outpaces most contemporary romances. Their riverside scenes mapping the cabin’s footprint with stones and lying by the water while the sky turns to ash-blue, wear the Terrence Malick influence openly, but Veloso’s boxy 3:2 compositions give them a sturdier, less floaty presence. It’s easy to understand why Robert clings to them for the rest of his life, which only heightens the tragedy to follow. Later, Bentley stages the wildfire as an environmental event of epic scale, with smoke and embers choking the frame and Robert’s nightmares folding into the real blaze. In those passages, the film connects the industrial world he helped build with the climate that is now turning on him.

A still from ‘Train Dreams’

| Photo Credit:

Netflix

Edgerton holds all of this together with a performance that is almost entirely about watching. He is in every scene, often speaking very little, registering the absurd talk of Apostle Frank, the generosity of Ignatius Jack, and the gentle, probing intelligence of Claire. You can see him trying to arrange a story in his head that makes sense of a wife and child gone in flame, and eventually a country that moves from steam to rockets while his own life calcifies around a cabin in the woods.

The late-life detour to Spokane, with Robert baffled by television images of John Glenn in orbit, is one of the few moments where Bentley’s Malick fandom produces something like its own language — the sense of a man who helped clear the way for the modern world, stranded in front of it like a tourist. Still, the final biplane flight does lean back into awards-season carpentry. As Robert floats and the montage cycles through his memories, Bryce Dessner’s strings swell and the narration ties a tidy bow with a life understood and a man finally “connected to it all.”

Train Dreams earns its praise for craft and performance, and every frame is composed with the conviction of artists who know what they’re doing. But in turning a thorny American ghost story into a handsome elegy, the film leaves intact the systems it mourns. It’s gorgeous work, no question, but you can feel the film checking its own seams instead of letting anything meaningful truly rupture.

Train Dreams is currently streaming on Netflix

Published – December 09, 2025 05:49 pm IST