Traditional Dogri craftsman Raza Khan, making a Dogri suit once adorned by queens, preserving the essence of Dogra culture, in Jammu on October 4.

| Photo Credit: ANI

The story so far: Human society is rapidly moving towards the extinction of its linguistic heritage. In India, the threat of extinction lurks over many indigenous languages. According to one report by UNESCO, India has topped the list of countries with the maximum number of dialects on the verge of extinction. With English as the academic lingua franca, many local languages have been pushed to the margins. According to D.G Rao, former Director of the Central Institute of Languages (CIIL), India has lost over 220 languages in the last 50 years.

Is Dogri in decline?

In recent years, growing concern has emerged over the gradual decline of the Dogri language in the Jammu region. Around the world, indigenous languages are being pushed to the margins, overshadowed by dominant tongues. Globalisation, migration, and the pursuit of economic opportunity often encourage speakers to prioritise widely used languages, while regional ones fade into disuse. Political choices and a lack of active interest among native speakers further deepen this crisis. Against this backdrop, Dogri finds itself at a crossroads. Although the J&K Official Languages Bill, 2020 gave it the long-overdue recognition as one of the Union Territory’s five official languages — alongside Urdu, Kashmiri, Hindi, and English — its status on paper has not translated into meaningful presence on the ground. Unlike other regional languages that have secured space in school curricula or administrative use, Dogri remains largely absent from classrooms and formal education.

Why is Dogri not being spoken?

The decline of Dogri in the Jammu region can be looked at through three critical lenses — government policy, generational perspectives, and the rural-urban divide.

One of the central reasons for the decline of Dogri lies in the absence of sustained government support. Unlike Urdu, Kashmiri, and Hindi, Dogri had to wait until 2003 for constitutional recognition. This long delay meant that by the time Dogri gained official status, it had already fallen behind in terms of institutional backing and visibility. A survey conducted by the authors further underscores this policy gap. The research employed a random sampling method, selecting households at intervals of three to four units to ensure representativeness. The sample was distributed across 20 different locations in the Jammu region; 130 people filled the survey form completely.

Nearly half of the respondents (48%) from the Jammu region believe that the government has failed to provide adequate policy support for Dogri, particularly in relation to its inclusion in school curricula and the creation of platforms for its growth. Another 43.2% felt that the language offers little relevance for employment prospects or career advancement, pushing individuals to invest their energy in learning languages perceived as more economically rewarding.

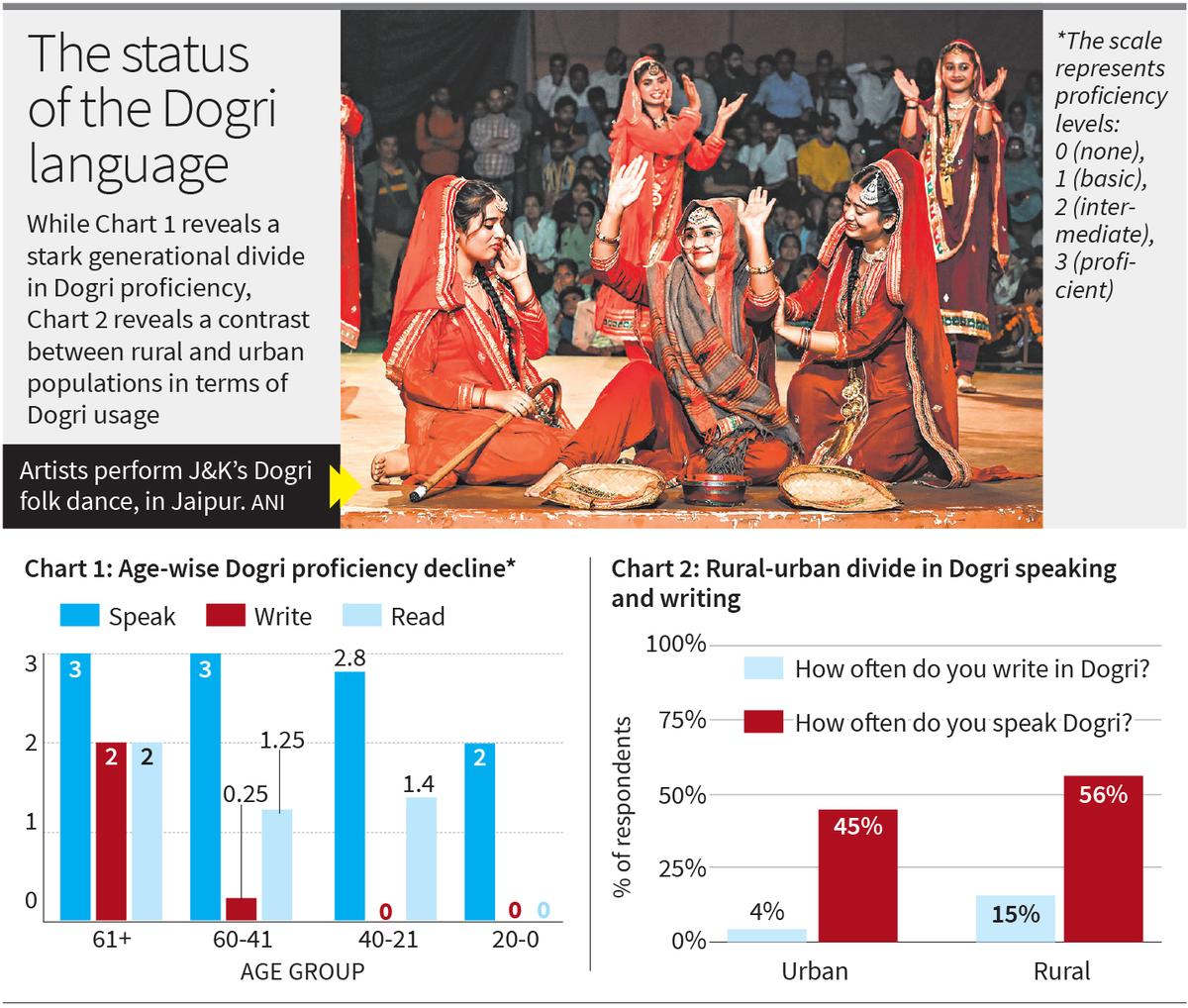

Additionally, Chart 1 reveals a stark generational divide in Dogri proficiency. The oldest respondents, those aged 60 and above, display the strongest connection to the language, with full proficiency in speaking (score of 3) and an intermediate score in reading and writing (average score of 2). This generation, raised in an environment where Dogri was central to daily life, continues to act as the language’s strongest custodians. However, the picture changes dramatically the lower you go in the age ladder. Among respondents aged 41-60, writing proficiency drops sharply to just 0.25%, reflecting the gradual erosion of literacy in the language. The decline becomes even steeper in the 21-40 age group. Respondents under 20 years of age show 0% proficiency in both reading and writing Dogri — effectively severing the language among the youth.

The survey also revealed a striking contrast between rural and urban populations in terms of Dogri language usage. As shown in Chart 2, approximately 56% of respondents from rural areas actively speak Dogri, with around 15% demonstrating the ability to write it. In contrast, among urban respondents, only 45% reported speaking Dogri, and only 4% had any proficiency in writing it. Many rural parents actively encourage their children to speak the language and maintain cultural continuity. Urban respondents displayed a more dismissive attitude toward Dogri, often viewing it as less relevant in modern, cosmopolitan settings.

What is the way ahead?

Like Dogri, many other indigenous languages, especially those spoken by tribal communities, are facing extinction as a result of reduced intergenerational transmission, political neglect, and cultural assimilation. Karan Singh, Maharaja of Jammu & Kashmir and former Education Minister of India, rightly observed that learning new languages should not come at the cost of ignoring one’s mother tongue.

To address India’s linguistic crisis, two challenges must be addressed. First is technical — with the 2021 Census on hold, we lack updated data on how many languages are endangered, and where urgent intervention is needed. Without this knowledge, both awareness and policy remain adrift. Secondly, one must shed the mindset that equates English alone with progress. The decolonisation of linguistics is the larger task at hand.

Rohan Qurashi is a research student at St. Stephen’s College, Delhi. Heena Chaudhary is a Phd scholar.

Published – October 28, 2025 08:30 am IST