For Telugu cinema, 2025 was a year of split screens with glittering highs at the box office on one side, and a shadowy underworld of leaks, hacks and digital theft on the other. While some films soared and others sank, the real plot twist unfolded far away from theatre halls.

Behind the scenes, a coordinated, sustained effort by the Telangana police, the Indian Cybercrime Coordination Centre (I4C) and the Anti Video Piracy Cell (AVPC) of the Telugu Film Chamber of Commerce quietly closed in on the industry’s most elusive pirates.

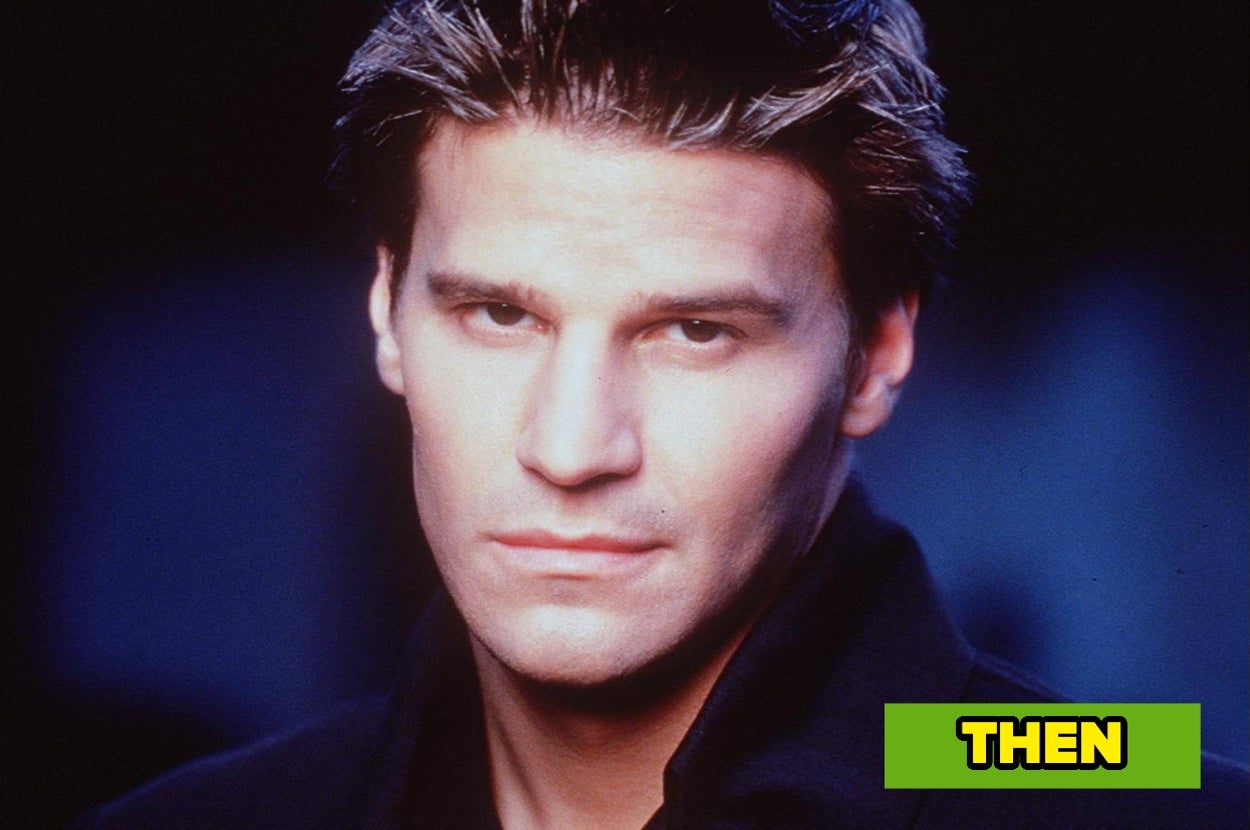

By the time the net tightened, several key operators had been tracked and cornered, including Cyril Raja Amaladoss, who funnelled fresh releases to multiple syndicates, and then there was a more notorious name in circulation: Ravi Emandi of iBomma.

On October 17, after months of following his movements, Telangana police finally intercepted Ravi when he visited Hyderabad. According to the police, he helmed a piracy network built around iBomma, Bappam TV and more than 65 mirror websites hosting newly released Telugu films in crisp high definition (HD) prints. The scale was staggering: hard drives with 21,000 films in different languages were seized, and police estimate Ravi earned around ₹20 crore from the operation, money allegedly channelled into flats and plots. His bank accounts, holding ₹3.5 crore, have now been frozen.

But the piracy itself was only the opening act. As police dug deeper, they found a darker layer: users streaming pirated films on iBomma and its mirror pages were being quietly diverted to betting platforms, a pipeline that enabled identity theft, data mining and financial fraud.

Two of Ravi’s associates — web developer Duddela Shivajee and Susarla Prashanth — had been arrested in September. Ravi also figures among four other FIRs involving piracy, online cheating and data theft.

His arrest added to a string of earlier breakthroughs. In September, the cybercrime wing had nabbed five persons: Ashwani Kumar from Bihar, the kingpin who allegedly hacked servers of digital media companies to steal HD prints of new films; Cyril Infant Raj of Tamil Nadu believed to have managed piracy websites such as 1TamilBlasters and uploaded more than 500 films since 2020 via international servers, earning nearly ₹2 crore in cryptocurrency; Hyderabad’s Jana Kiran Kumar, accused of recording over 100 films inside cinemas with concealed mobile devices; Sudhakaran from Erode who confessed to recording 35 south Indian titles; and Arsalan Ahmed who allegedly uploaded films on file-sharing platforms and circulated them through Telegram channels.

A definite move

The wave of arrests and continued crackdown on piracy come on the heels of fresh triggers. The AVPC had filed complaints after Telugu films #Single and HIT: The Third Case appeared online on the very day of their release, followed soon after by a similar leak of Kuberaa. Each incident renewed pressure on enforcement, signalling that the pirates were growing bolder and more sophisticated.

According to investigators, the syndicates thrived behind layers of digital camouflage: encrypted Telegram groups, overseas domain-hosting servers and cryptocurrency payment trails that blurred their footprints across jurisdictions.

The recent arrests have injected a sliver of hope into the industry, but the battle is far from over. For every iBomma or 1TamilBlasters that is pulled down, several more hydra-like networks are at work, waiting to fill the vacuum.

The AVPC has pegged the loss of revenue to the industry in 2024 due to piracy at ₹3,700 crore. An estimation of losses for 2025 will be carried out by the end of the year, although chairperson Rajkumar Akella is hopeful that the numbers may just dip this time.

“Tackling piracy is a long-drawn, sustained battle,” he says. “Several rogue websites such as 1Tamilmv, Movierulz, Tamilrockers and CineVood continue to thrive. The recent arrests have shown that if all of our efforts continue, there will be results.”

While pirated links of new releases, including Andhra King Taluka and Tere Ishk Mein, continue to surface online, there is a faint silver lining, notes Rajkumar. Most of those prints are not razor-sharp HD versions anymore. Earlier incidents of films, such as HIT 3, Single and Kuberaa, appearing online on or before release day had rattled the industry, but now the uploads are making their way online nearly two days after a film hits theatres. “Yet, it is disconcerting,” he admits.

The tightening of the noose is visible. With Telangana police working in coordination with the I4C, Rajkumar says the industry has begun to see measurable impact: “Police alerted us to certain leak points and we upgraded the standard operating procedures for digital cinema suppliers to plug these loopholes. This has helped. Further, apart from one incident in Dharmavaram in Anantapur district, there have not been any reported cases of new films being pirated with camcorders inside theatres in the two Telugu States over the past two months.”

But the trail doesn’t end within regional borders. Newer piracy links from camcorder prints have been traced to Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and other States, often in remote locations where security measures tend to be lax.

Unlike the pre-digital era when curbing piracy meant tracking down lone operators, the recent spate of arrests has helped expose the modus operandi of large scale networks.

How it all began

The vast network of digital piracy first came into focus during the release of Baahubali 2 in 2017. Rajkumar recalls how the case of Priyank Paradeshi, an IT employee based in San Francisco, exposed the scale of a distributed, cross-border operation. Paradeshi reportedly worked with associates who recorded films on camcorders in Kolkata, while another member of the network threatened Hindi film production houses, demanding hefty payments to prevent leaks of their upcoming releases.

“This was the time when we could still track IP addresses, before pirates started masking them,” Rajkumar says. “We followed the trail to Jabalpur and Pune. Transactions were being carried out using cryptocurrency even in 2017. That showed us the complexity of the issue. At the time, jurisdictional challenges made it difficult to apprehend culprits across geographical locations.”

The Ministry of Home Affairs-backed I4C, he says, has helped bridge those gaps.

To put things in perspective, he points to the case of iBomma Ravi, who was eventually arrested when he briefly visited Hyderabad. “If he is living in France and outsourcing his work to the Caribbean Islands, how do we nab him without the help of local authorities?”

Investigations revealed the vastness of Ravi’s operation: the iBomma and Bappam domains were handled by employees in the Caribbean and the UK. According to the police, Ravi admitted to purchasing movies via the Telegram app to upload them to the domains. He also recorded films from OTT platforms and converted them into HD quality through a multi-layered, auto-generated mirror transmission system. The servers supporting the network were operated from the Netherlands and Switzerland.

Investigators found that Ravi had initially registered the iBomma domain with his own e-mail ID, debit card and personal details through a company named Njalla. The site was later hosted on IPVolume, which provided backend infrastructure. Its underlying script redirected users who clicked on movie links to online gaming and illegal betting platforms before granting access to the pirated film.

Transnational poly crime

Long dismissed as a “victim-less crime”, piracy was rarely considered serious enough to warrant the involvement of law enforcement agencies across borders. But as Rajkumar describes it, piracy has now evolved into a “transnational poly crime”, a sprawling nexus that intersects with betting syndicates, identity theft and malware attacks, compelling global agencies to take note.

In July, the Digital Piracy Conference at the Indian School of Business, Hyderabad, attended by officials of the Central Bureau of Investigation and Interpol, focussed on this growing nexus between piracy and cybercrime. The arrest of iBomma Ravi, and the subsequent revelation of how the site exposed users’ financial and identity data to betting networks and fraud portals, is a case in point. “Anyone arguing that watching movies on piracy websites does no harm needs to understand that movie piracy is just a front; identity theft and malware affects every user,” says a producer working closely with the AVPC.

Producer Sureshbabu concurs. “It is good that the government is helping us combat piracy. The larger issue is to make people realise the gravity of the issue. Apart from the makers incurring loss, their privacy is compromised.”

These concerns were reiterated internationally. At the Interpol Global Meeting on Digital Piracy held in Seoul, Korea, on November 17 and 18, the need for global enforcement agencies to stay connected and exchange knowledge for actionable intelligence was a key theme, Rajkumar says. “If cinema is going global, so is piracy.”

Piracy and malware

In 2021, cryptomining malware was discovered embedded in pirated downloads of Spider-Man: No Way Home, compromising both individual devices and corporate networks.

“If just one piracy syndicate (iBomma) was making nearly 25 lakh per month, it shows the magnitude of the problem. Betting apps linked to the network have been benefitting from the traffic to the piracy site,” Rajkumar reiterates.

On November 27, the Telugu film industry, with the help of the Telangana government, signed a memorandum of understanding with the Japanese film and anime organisation CODA (Contents Overseas Distribution Association) to strengthen protection for intellectual property and take up counter measures against online copyright violations. The MoU assumes significance given the rising popularity of Japanese anime in India.

For Rajkumar, the larger battle now is to hold intermediaries, such as web-hosting companies, accountable. “When piracy links surface, complaints are raised with the hosting domains, and it takes 24 to 36 hours to bring down the links. By then, the damage is done since hundreds of mirror websites will already have those links. We are developing tools to escalate the issue in real time to the hosting domains.”