Yeh haath mujhe de de Thakur… Thankfully, Gabbar never sought the meticulous hands of film restorers and archivists who were busy rescuing the brittle frames of Sholay, which will soon be released in a restored 4K version as Sholay: The Final Cut.

“Sholay: The Final Cut, is the original uncut version that audiences will get to experience for the first time ever,” says Shehzad Sippy, CEO and MD, Sippy Films, referencing the “original ending”. When Sholay was first released in 1975, the censor board — then under the purview of Indira Gandhi’s Emergency — insisted on changing the ending.

“The idea of a former cop killing Gabbar and taking the law into his own hands alarmed them. My grandfather, GP Sippy, even tried to persuade the IB ministry, but, realising that the movie had already gone 3X over budget, and was almost three years in the making, a re-shoot was ordered, resulting in the alternate version the world has known for 50 years. But that changes now,” Shehzad says, hinting at the inclusion of additional scenes, such as the sequence depicting Ahmed’s killing.

Optimistic that the restored version will bring in audiences to theatres, he says, “The central themes of friendship and good versus evil still resonate. The younger generation, inundated with some of today’s mediocrity, will understand why this is a timeless classic,” adds Shehzad.

(above) A combination picture that shows a still from Sholay before and after the restoration and (below) The film of Sholay being restored

| Photo Credit:

Film Heritage Foundation

Behind every film restoration lies a detective story — of scavenger hunts for long-lost reels, led by cinephiles determined to keep India’s cinematic legacy alive.

Auteur Guru Dutt — notorious for his perfectionism — would have been perturbed to learn that the original negative of Bharosa (1963), a film in which he had a starring role, resurfaced at a scrap dealer’s shop, wedged between dormant film magazines and discarded VHS cassettes. Elsewhere, reels of Uttam Kumar-Vyjayanthimala starrer Chhoti Si Mulaqat (1967) and Gulzar’s Maachis (1996) were discovered stacked against shanty walls, leaning against clotheslines in a bylane of Mumbai. These film cans get repurposed as makeshift kitchen utensils.

Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, founder of the Film Heritage Foundation (FHF), has spent years chasing the ghosts of Indian cinema — lost negatives, shredded reels, prints covered in mould — in the most improbable spots: flea markets, warehouses and old movie theatres.

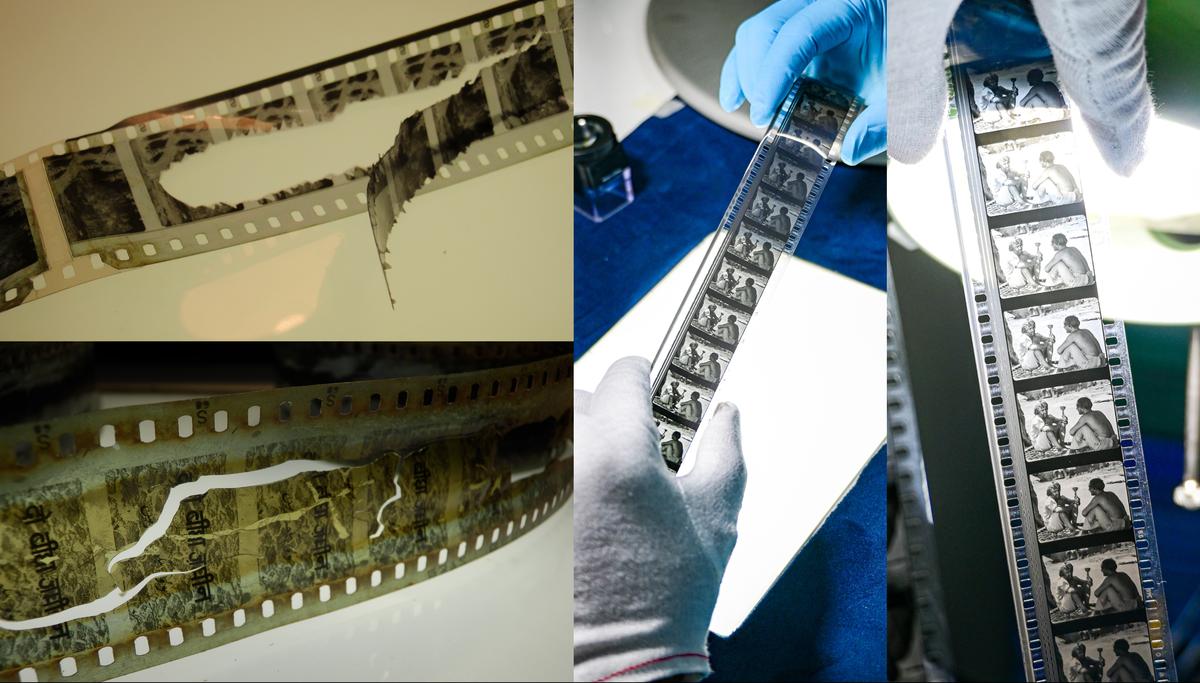

Restoration involves identifying the best source material, inspecting, cleaning, and repairing it, and finally, scanning it frame by frame, he explains. The digital clean-up and colour correction happen later. Restorations generally cost anywhere between ₹35 and ₹50 lakhs, depending on the condition of the material, Dungarpur notes. While Sholay is funded by the producer, a few others are funded by Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, George Lucas’ foundation and FHF.

But sleuthing is not just confined to the technical aspects. “Consulting surviving crew members is equally important,” says Dungarpur. He particularly goes digging for director’s notes or diaries, lobby cards, song booklets and shot breakdowns. “They offer clues to bridge any gaps of information left by damaged footage,” he says.

The restoration of Sholay turned out to be as dramatic as the movie itself. In 2022, the film’s director Ramesh Sippy and his son Rohan reached out to Dungarpur to help locating the negatives. They connected him with Shehzad, who then initiated discussions regarding the restoration. “He indicated that some of the film elements were stored in a Mumbai warehouse. Upon examining the contents of the film cans, we discovered that they contained the original 35mm camera and sound negatives of the film,” Dungarpur recalls.

Shehzad then informed FHF about additional film elements, including the original ending, stored with Technicolor (a post-production lab) in London — something his father, Suresh Sippy, had mentioned before passing away in 2021. “The British Film Institute assisted with assessing these reels, after which they were transported to L’Immagine Ritrovata, a film restoration laboratory, in Bologna,” says Shehzad.

The restored uncut version of Sholay being screened at Il Cinema Ritrovato 2025 in Bologna

| Photo Credit:

Film Heritage Foundation

One of the biggest discoveries was the original four-track magnetic sound, Shehzad says. “It is one of the best formats for persevering audio — we were lucky to recover it in Mumbai and bring all the original sound back into the film.”

The restoration that predominantly utilised the interpositives located in London and Mumbai proved to be a complex endeavour, spanning nearly three years as the original camera negative was severely deteriorated, says Dungarpur.

Elsewhere, the hunt for cinematic gems continues. For Dungarpur, the ongoing restoration of Pakeezah(1972), expected to be completed in a year, feels deeply personal. His love affair with the movie began as a child when his maternal grandmother, Usha Rani, Maharani of Dumraon (an erstwhile zamindari state in Bihar), would book entire cinema halls just for the two of them. “I remember watching Meena Kumari lighting up the screen in ‘Inhi logon ne’.”

Today, he has allies in producer Tajdar Amrohi and Rukhsar Amrohi, children of Pakeezah’s legendary director Kamal Amrohi. The discovery of the film’s negatives reads like a Bollywood plot. They stumbled upon them by accident — in a lab — while looking for another classic, Daaera (1953), also directed by their father. “Then suddenly, there it was, in a dilapidated condition, but still salvageable. The city’s humidity too adds,” Rukhsar says, scrolling through the photo of rusted cans.

The original reel of Pakeezah that was found in a dilapidated condition

| Photo Credit:

Bilal Amrohi

Tajdar informs how the prints were scattered all over, each version slightly different from the other, with even different run times. “Back in the day, individual exhibitors would chop off reels to make films shorter, which meant more screenings. This means that decades later, we are left with a patchwork of mismatched reels and missing frames,” he says.

The siblings pinned their hopes on Dungarpur’s FHF to revive his father’s legacy, which will also make its way to Bologna. Tajdar is conflicted between emotion and pragmatism — a son preserving his father’s legacy and a producer thinking about box office. “We are planning a calculated re-release — a two-week theatrical run and festival screenings,” he says, adding, “We may revisit the film at the editing table once it is restored to pace it differently for modern-day moviegoers.”

The reel of Pakeezah being restored

| Photo Credit:

Film Heritage Foundation

He is optimistic that the timelessness of Pakeezah’s storytelling will still resonate, a film that is as tragic off-screen as it was on-screen. “It has survived so much — Meena Kumari’s failing health, the separation of my father and her in 1964 that halted production, and her passing soon after release,” reminisces Tajdar, who would visit the set often as a 23-year-old.

The same fate awaited the three-year restoration of Do Bigha Zamin (1953), driven by Criterion Collection and Janus Films in collaboration with FHF. The team accessed the original negatives deposited by the Bimal Roy family at the NFDC-National Film Archive of India for preservation. “The elements had deteriorated over time with huge tears, damage from mould, heavy watermarks,” Dungarpur shares. The conservators repaired every inch before shipping the reels to L’Immagine Ritrovata. Rescue also came from another quarter when a combined dupe negative from the 1950s was found at the British Film Institute, which was then used to complete the film’s restoration.

The reel of Do Bigha Zamin being restored

| Photo Credit:

Film Heritage Foundation

Restoration makes a larger revelation: cinema is fragile, but can still endure. And audiences too are responding in favourable ways. For graphic designer Ashutosh Vyas (29), who watched the FHF’s restored version of Manthan (1976), the socio-economic politics of the film still resonate: “The moviegoers of today are fatigued by formulaic narratives. And then to learn that both director Shyam Benegal and cinematographer Govind Nihalani were involved in the restoration makes it even more special.” To him, a restored Pakeezah would not be nostalgia, but discovery.

Late filmmaker Shyam Benegal, with Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, checking out the restored reels of his film Manthan

| Photo Credit:

Film Heritage Foundation

In the end, the restoration of such movies tells a larger story: while films are celebrated on screen, they are equally neglected. But the hunt for their lost reels is nothing short of a Bollywood potboiler, unfolding suspense, emotion, drama, and then, redemption.