The journey of Goods and Services Tax (GST) implementation has entered a major new stage with the latest restructuring of tax slabs, a move expected to pass on over ₹2 lakh crore in tax benefits to consumers. With this, the GST compensation cess stands abolished as it merges with the regular tax, marking the end of an era of compensation under GST. The decision is likely to boost local demand, and the consequent growth in revenue may reduce the expected revenue loss. However, certain States feel that no proper estimation of this loss has been made, and that the actual loss could be much higher than projected. They are aggrieved that their demand for compensation has been ignored.

Though studies show that GST implementation has largely benefited all States through liberal compensation mechanisms, the post-compensation tax structure is expected to raise concerns in some of them. The cess and surcharge mechanism gives the Centre additional leverage over the States. With significant changes in the fiscal policy landscape in recent years, including the introduction of GST, which has effectively shifted taxation power from the States to the GST Council, there is an increasing demand to revisit the fiscal policy on tax sharing to live up to the principle of ‘cooperative federalism.’

Evolving tax landscape

Fiscal policy in India, particularly on revenue sharing between the Union and State governments, is an evolving story. Article 246 of the Constitution (subject-matter of laws made by Parliament and by the legislatures of States) demarcates the areas of taxation power between the Centre and the States under the Union List and the State List, respectively, with residuary power reserved for the former. Using this residuary power, Parliament amended the Constitution in 2016 through Article 246A for the levy of Service Tax. The tax landscape changed with the introduction of the Service Tax through the 92nd Amendment, and further with the 101st Amendment, through which GST was launched in July 2017.

For the first time, GST introduced a destination-based tax instead of an origin-based one, besides allowing the Centre and the States to share a common tax base. With GST being a contributor of substantial own tax revenue to States, this new regime has led them to suffer a significant erosion in their fiscal autonomy, as the power on taxation is shifted to the GST Council, where the Centre dominates the decision-making process.

As India is a multi-tiered government, design asymmetry arises in assigning resources and responsibilities between the Centre and the States. Normally, the power to raise resources is largely centralised for efficiency and economic reasons. The expenditure responsibilities are decentralised for better accountability and efficient delivery of public services. The resulting fiscal imbalances are corrected through re-assignment and redistribution, enabling the government at each level to command resources to discharge its responsibility. Such an adjustment must remain dynamic to address changes in the fiscal landscape.

Role of Finance Commission

Articles 268 to 293 of the Constitution define the Centre-State financial relations. The Finance Commission (FC) is constituted under Article 280, which has been constitutionally assigned the task of determining transfers to all States. However, there are grievances regarding the manner in which the Central Finance Commission applies its tax-sharing criteria, which, according to some States, penalise progressive ones. There are also complaints of inconsistency among the Finance Commissions in adopting criteria and applying relative weights.

The Commission’s grants are supplemented by grants under various Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS), Central Sector Schemes, and, earlier, by the Union Planning Commission (PC) grants, which ceased after the abolition of the Planning Commission in 2014. Article 282 provides for direct grants by the Union government, while Article 275 provides for statutory grants through the Finance Commissions. Some States feel that the flow of funds through these channels is neither fair nor transparent.

Falling devolution share

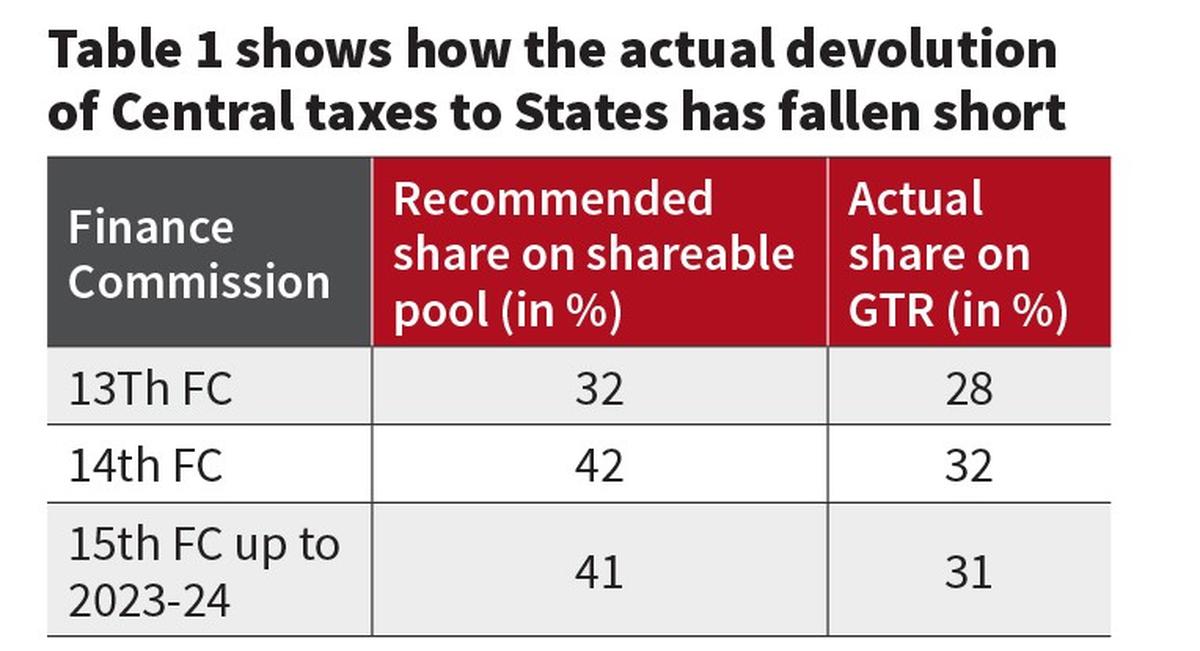

The earlier system of sharing individual taxes was replaced by a global sharing principle, thanks to the 80th Amendment that came into effect during the 11th Finance Commission (2000-2005). The Commission recommended 29.5% to the States out of the proceeds of shareable Central taxes, which was steadily enhanced to 30.5% by the 12th Finance Commission, 32% by the 13th Finance Commission and 42% by the 14th Finance Commission. In view of Jammu and Kashmir having ceased to be a State, the share came down to 41%. However, despite higher recommendations, the actual devolution to the States as a percentage of Gross Tax Revenue (GTR) has consistently fallen short (Table 1).

The shortfall is attributed to the ever-increasing cesses and surcharges, which are not part of the shareable pool of revenue. The cess and surcharge accounted for ₹3,86,440 crore as per the Revised Estimates (RE) 2024-25. It is expected to be ₹4,23,456 crore under the Budget Estimates (BE) for 2025-26, excluding the GST compensation cess. States have been constantly pressing for their merger with the shareable pool, a demand the Union government has not accepted. This resource gives additional leverage to the Centre in managing its expenses over and above its usual tax share, as the proceeds from cesses and surcharges often fund the Central share in various schemes.

Dependence on Central transfers

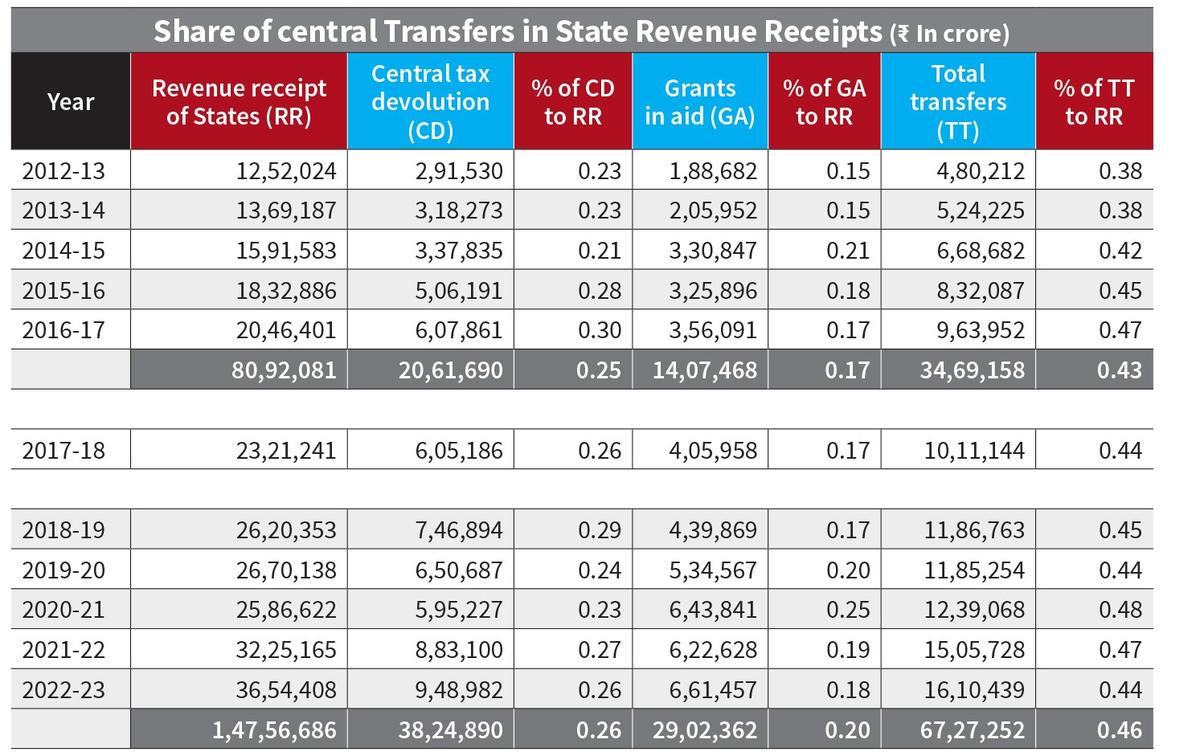

Central transfers still account for 44% of the States’ revenue receipts. It ranges from 72% for Bihar to 20% for Haryana with nine States — Haryana (20%), Telangana (21%), Gujarat (28%), Maharashtra (28%), Karnataka (31%), Tamil Nadu (31%), Goa (33%) Kerala (34%), and Odisha (41%) — getting less than the overall average figure of 44%. This indicates heavy dependency of States on Central transfers and, to that extent, a compromise in their fiscal autonomy.

A look at the proportion of tax revenue shared between the Centre and the States during pre- and post-GST periods reveals a clear trend: the power to levy taxes is getting centralised, while the expenditure responsibilities on the States are on the rise (Table 2).

For the five years from 2012-13 to 2016-17, the pre-GST period, the Centre collected 67% of the total tax revenue, while the States collected 33%. During the post-GST period (2018-19 to 2022-23), the ratio remained unchanged. As for revenue expenditure, the Centre incurred 47% and the States 53% in the pre-GST era. During the post-GST period, the figures were 48% and 52%, respectively. Increases in the Centre’s revenue expenditure in recent years are largely attributed to the expansion of CSS on subjects that mostly fall in the domain of the States.

The expenditure commitments of the States are comparatively higher, as they are responsible for tackling the subjects of law and order, health, education, agriculture, and local self-government. As a result, States seek power to collect higher tax revenues, as the present fiscal policy of taxing power does not adequately address their requirements. Further, heavy dependence on Central transfers also creates problems such as liquidity management and the fear of political vendetta on the Opposition-ruled States.

As a way out, some States suggest that the example of Canada be followed where the federal government collects 46% of tax revenue and spends 40%, while sub-national governments collect 54% and spend 60%. Such a system gives more financial autonomy and flexibility to the States.

With rising public aspirations and widening service gaps, States’ expenditure commitments are steadily increasing. GST introduction has altered the resource position of the States, in addition to centralising the authority to levy tax. The heavy dependence of the States on the Centre is creating friction, especially in the Opposition-ruled States. This is why many States and economists are calling for a restructuring of the tax sharing principle to enhance the States’ fiscal autonomy.

Towards fiscal autonomy

States like Tamil Nadu have appointed a committee to examine Centre-State relations. It is against this backdrop that the recommendation is being made to share the tax base on personal income tax (IT) between the Centre and the States, on the lines of the GST. For instance, the share of Central tax devolution to States as per the 2025-26 Budget Estimates is ₹14,22,444 crore. If the personal IT base of ₹13,57,000 crore (BE 2025-26) is shared on a 50:50 basis with States where tax is collected, the Central tax devolution share to the States would effectively get reduced to ₹ 7,43,944 crore.

Alternatively, it is also suggested to empower the States to top up IT, without major changes to the current system of levy and collection.

Such an arrangement would reduce States’ fiscal dependence on the Centre, improve liquidity, and allow progressive States — which contribute more tax revenue — to directly benefit from their higher tax base. The Centre will still have substantial leverage in resource sharing to correct fiscal imbalances, if any, through Central schemes, grants and usual tax devolution.

K. Shanmugam is a former officer of the Indian Administrative Service. He served as Chief Secretary of the Tamil Nadu government during 2019-21, after being the State Finance Secretary from 2010 to 2019